Laurel

and

Hardy

aren't

the

only

comedians

who

had

to

eat

shoe

leather

-

but

that

was

because

they

were

too

poor.

The

Armenian

Quarter

had

more

than

its

share

of

comedians

-

in

their

closed

society, laughter was an indispensable binding knot.

Jordan

(Marashlian)

Chilingirian

was

among

the

most

accomplished

and

incorrigible

pranksters.

His performances could have qualified him for an Oscar with their impeccable rendition.

There

was

the

time

the

venerable

matriarch,

Anna

Baghsarian

(Im

Arakel),

lay

in

bed

with

a

mild

attack

of

indigestion.

There

was

no

real

health

issue,

and

she

could

have

easily

gotten

over

it

by

taking a pinch of cumin.

Jordan happened to be visiting and he had a sudden brainstorm.

"Let's

play

a

trick

on

her,"

he

whispered

conspiratorially,

out

of

her

hearing,

to

Im

Arakel's

brood

gathered outside the room.

There were chuckles coupled with admonitions not to get carried away.

"Don't worry," Jordan reassured them. "She'll be fine."

He

got

the

women

to

rummage

around

and

find

a

white

robe

and

a

hat.

Then

he

fashioned

some

sort

of

stethoscope

out

of

a

bit

of

yarn,

and

put

on

dark

spectacles

(he

might

might

have

painted

a

beard

on,

for

good

measure.

[Burning

the

end

of

a

cork

from

a

drink

bottle

and

using

it

as

a

brush

was

an

excellent

way

of

painting

a

face

black.

The

strokes

had

to

be

applied

as

soon

as

the

flame

died

-

it

would

not

work

so

well

if

the

cork

was

left

to

cool.

There

was

the

smell,

though,

that

one

had to put up with, but it was a minor sacrifice for a good disguise].

Jordan

was

not

worried

about

detection.

Im

Arakel

had

poor

eyesight

and

he

knew

she

would

not

be able to place him.

Mimicking

a

Greek

doctor

speaking

Arabic,

with

a

lot

of

aspirant

"Khabibi"

[i.e.,

"habibi",

the

Arabic

for

'loved

one'),

Jordan

shuffled

into

the

room

and

proceeded

to

examine

his

patient,

surrounded by an audience of giggling relatives.

When

he

had

finished

his

ministrations,

he

dug

into

his

pocket

and

came

out

with

a

20

mils

piece

[the

currently

in

use

during

the

British

Mandate

of

Palestine],

and

placed

it

in

the

palm

of

the

astonished woman.

"What

a

wonderful

doctor,"

Im

Arakel

enthused

after

Jordan

had

disappeared

(only

to

return

and

rejoin

the

group,

minus

the

disguise).

"He

not

only

examines

and

prescribes

medicine,

he

also

gives

out money to his patients."

Im

Arakel,

the

widow,

was

an

insomniac.

When

the

weather

was

amenable,

she

would

go

walkabout

the

alleys

of

the

Armenian

Quarter,

sometimes

losing

track

of

time.

As

she

grew

older,

she

would

push

a

chair

ahead

of

her

(there were no walkers to be had then) for support.

There

were

few

people

about

during

her

nightly

peregrinations.

But

one

night,

as

she

made

her

way

along

the street, she happened to notice some unusual activities near the door of a house.

Ever

curious,

she

approached

the

group

of

men,

their

heads

and

faces

hidden

in

the

distinctive

Arabic

"kefiyyeh"s.

Interrupted

in

their

nightly

malfeasance,

the

burglars

paused

for

a

second

to

deal

with

this

unexpected

complication.

One

of

them

detached

himself

from

the

huddled

group,

pulled

Im

Arakel

aside,

and

whispered

to

her,

in

no uncertain terms: "Im Arakel, get yourself home."

They

knew

who

she

was.

They

would

have

been

casing

the

joint

for

some

time

before

deciding

to

make

their move.

Im Arakel wanted to know what they were doing, but the burglar set her firmly on her course home.

"It's better if you forget what you saw tonight," he warned her.

The

Armenian

church

in

Jerusalem

traditionally

celebrates

Christmas

on

January

19,

following an ancient calendar.

The

day

before,

the

Armenian

Patriarch

travels

in

an

official

convoy

to

Bethlehem,

accompanied

by

members

of

the

priestly

brotherhood.

They

are

met

at

the

Greek

Orthodox

convent

of

St

Elias

(Mar

Elias),

a

mile

or

so

from

the

city

entrance,

by

a

cavalcade

of

mounted policemen, a guard of honor, and the mayors of Bethlehem and Beit Jala.

The

pilgrims

are

invited

to

break

bread

with

the

reception

committee

(they

are

welcomed

with

an

offering

of

bread

and

salt).

Then

the

entourage

wends

its

way

to

the

Church

of

the

Nativity

in

Bethlehem,

through an avenue of pilgrims and Armenian scout bands.

The

Armenians

hold

their

prayers

in

their

convent

there,

then

the

Patriarch

returns

to

Jerusalem

by

himself.

The

priests

remain

in

the

Armenian

section

of

the

Nativity

church,

awaiting

the

return

of

the

Patriarch who will officiate at the traditional midnight mass.

During

the

Jordanian

administration,

pilgrims

would

travel

to

Bethlehem

in

Arab

buses,

since

practically

few

had

their

own

private

car.

They

would

spend

the

rest

of

the

day

there

until

it

would

be

time

to

attend

the midnight mass which is broadcast around the world.

In

the

old

days,

the

Armenian

church

provided

the

pilgrims

with

dinner:

usually

"patcha"

(mutton),

boiled

and

seasoned

in

a

huge

cauldron

which

now

occupies

pride

of

place

in

the

Edward

and

Helen

Mardigian

museum in Jerusalem.

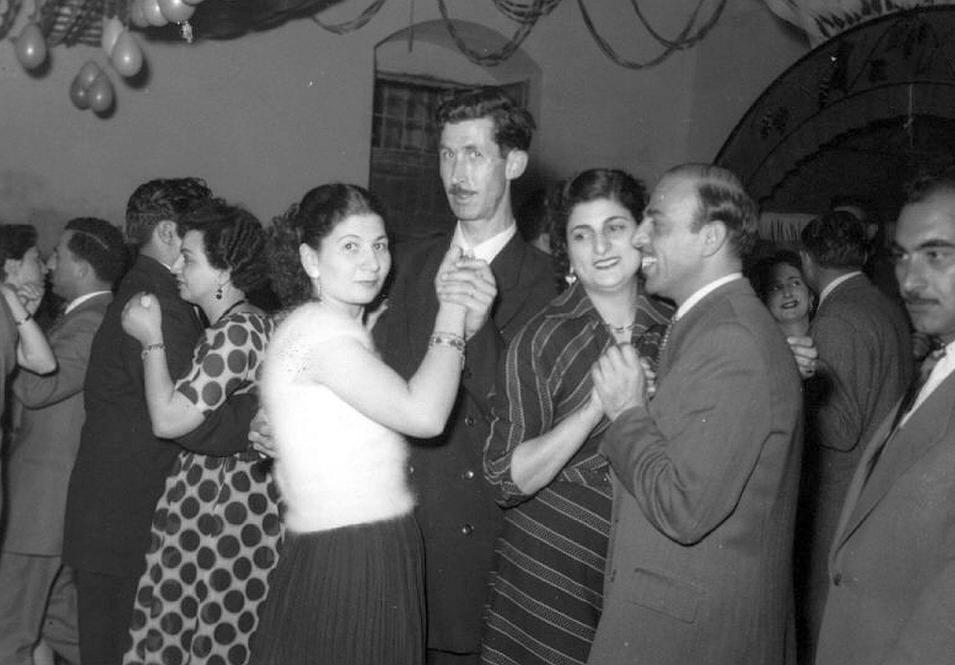

One

Christmas,

a

group

of

enterprising

Armenian

youths

staged

a

soccer

match

on

the

roof

of

the

church,

using someone's boot for a football. The game got quite spirited.

The

chef,

stirring

the

"patcha"

near

the

makeshift

goal,

paused

to

watch,

before

returning

to

his

duties.

He

bent

to

pick

up

something,

and

it

was

at

that

precise

moment

that

someone's

energetic

kick,

propelled

the "football" smack into the middle of the bubbling cauldron.

It

is

said

it

was

only

when

the

chef

was

serving

dinner,

that

the

boot

surfaced,

on

the

plate

of

some

hapless pilgrim.

Among

its

many

enterprising

endeavors,

the

Jerusalem

Armenian

Benevolent

Union

(JABU)

managed

to

obtain

a

licence

to

operate

a

movie

theatre,

making

use

of

its grand hall.

The

first

movie

to

be

shown

was

The

Greatest

Show

on

Earth,

starring

Charlton

Heston,

Gloria

Graham

and

James

Stewart.

It

was

in

spectacular

color,

and

tickets

were

sold

out

within

minutes of its opening.

A

makeshift

projection

room

had

been

constructed

at

the

back,

supported

on

pillars.

There

was

also

room for the projectionist (who happened to be Greek) to entertain special guests he had invited.

But

the

architects

and

builders

must

have

miscalculated,

for

one

day,

the

whole

structure

came

tumbling

down, people "upstairs" landing in the laps of hapless members of the audience below.

We

were

little

children

at

the

time,

and

a

group

of

us

hovered

around

the

entrance

to

the

hall,

hoping

to

get a peek at the screen, without having to buy tickets for which we had no money.

Kevork

Kaplanian,

a

community

leader

who

owned

a

shoe-making

concern,

and

who

was

one

of

the

members

of

the

committee

that

orchestrated

the

rejuvenation

of

the

JABU,

acted

as

usher.

He

would

not

let

any of us little bludgers in until after the film had started and the hall was almost full.

But

eventually,

we

were

allowed

to

sneak

in,

and

enjoy

the

rest

of

the

show.

And

what

a

delight

that

was.

When

we

grew

older,

the

club

caterer,

"Abu

Ishaq"

(Hovagim

Koukeyan),

would

task

us

with

the

job

going

around with a tray full of confectionery, melon seeds and biscuits for sale during intermissions.

We were not paid for our work, but got to see the show for free.

The

day

came

when

the

last

of

the

British

prepared

to

march

out

of

the

land.

We

lined

up

the

streets

to

see

them

go.

I

was

standing

next

to

my

mother.

As

they

trooped out, a young soldier suddenly thrust a package at my mother:

It was a box of chocolates.

Why

he

singled

her

out

for

his

attentions

remains

a

mystery:

there

were

other

young

girls

and

women

among

the

gallery

lining

the

street

and

watching

the

exodus,

some

quite

pretty

no

doubt.

My

mother

stood

there

shocked

and

transfixed,

unable

to

move.

She

was

the

bashful

type

and

did

not

know

what

to

do.

But

her

neighbor,

Anna

el

Deredereh,

had

no

such

compunctions.

She

elbowed

my

mother

aside and snatched up the package.

The

soldiers

had

been

housed

in

Beit

Sirapion,

a

two-storey

building

in

the

Armenian

Quarter.

Chchildren

were

always

crowding

around

the

entrance

in

the

hope

of

getting

a

treat.

The

soldiers

obliged

by

tossing

handfuls

of

crackers

to

them.

The

biscuits

were

a

great

luxury

and

helped

assuage

the

pangs

of

hunger

at

a

time when no one knew where the next meal was going to come from.