Armenian Jerusalem

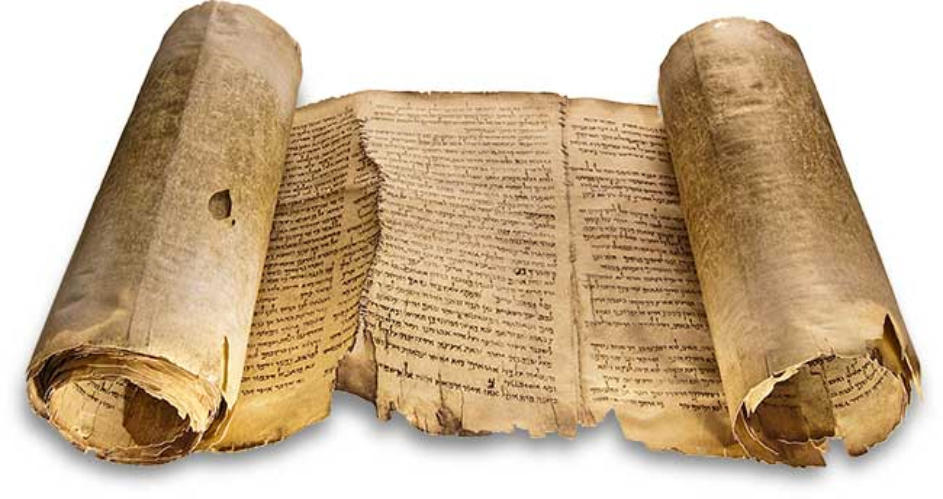

The Isaiah scroll

Six decades ago, an illiterate Arab Bedouin, his thick, black

moustaches' bristling with excitement, stumbled upon a treasure

trove in the parched wilderness of the Holy Land — and helped

inscribe a new page in the history of religion.

Mohammed el Dheeb (the Wolf) was out chasing a stray goat, back in 1944, but the priceless scrolls he uncovered, in the limestone caves of Qumran, near the shores of the Dead Sea, marked a turning point in his life-style. His tribe, the Ta'amra, increased and prospered, and the shadowy middlemen to whom they sold the ancient writings ensconced themselves in posh villas around the hills of Bethlehem. But the world of scholarship reaped the greatest profit and pleasure — deciphering, decoding, analysing and speculating, with still no end in sight. Incredulous archaeologists have been sifting through the accumulated debris and bat-droppings of two millennia for more scraps of ancient writings that may still be entombed — and the results have been staggering: thousands of fragments have been discovered in 11 caves, most written on parchment made from the skins of sheep and goats. Israeli archaeologists were in the vanguard of the scholarly blitz and the Israeli Government accorded their efforts official sanction by building a special Shrine of the Book to house the scrolls. The shrine, an adjunct of the Israel Museum, only a stone's throw from the centre of Jerusalem, has been built to symbolise the eternal struggle between the Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, so magnificently articulated in the Essene texts, some 700 of which have so far been put together. It has been a Herculean task: some of the scrolls were found in excellent condition, particularly those sealed in ceramic jars (fired in the Essene community's own kilns), where moisture was minimal, but others had developed a decaying' deep brown colour and some of the writing could be made out only with the aid of infra-red photography, as in the case of the Genesis Apocryphon, a version of the Book of Genesis, retold in Aramaic, the lingua franca spoken in the Middle East around the time of Jesus. Several years ago a full-scale scientific study of the scrolls was launched to 'discover "exactly what happens over the course of time to the parchments, why they tend to deteriorate, how best they can be preserved and, not least, whether they had deteriorated since they were first discovered," in the words of' curator Magen Broshi. The project, turned over to the Weizmann Institute, delved into uncharted territory, and got nowhere, until a comparison of infra-red spectra of the ancient parchment with new parchment bits revealed that in the deteriorated areas the collagen of the animal fibres had broken down, after coming into contact with heat and water. Institute scientists Wolfie Traub and Stephen Weiner developed a technique using x-ray diffraction, and were able to measure the extent to which collagen (a fibrous protein existing in all living matter) had already deteriorated into gelatine. Another scientific sleuth, Emanuel Gil-Av, joined the hunt — and it was finally determined that the scrolls had taken place over hundreds of years. Actually, it could even have started while the scrolls were still being used by the Dead Sea .sect. "We have found no evidence whatsoever that deterioration took place since the scrolls were taken from the caves," Weiner concluded. With a clean bill of health in their heads, the shrine's directors have now established a monitoring system to warn them if degeneration is resumed. And to slow down, possibly even to halt, decay, Broshi's staff keeps daily watch on the scrolls. Each fragment — even those not much bigger than a pencil point — has been bedded between sheets of highly absorbent rice paper, laid between sheets of heavy cardboard and kept in complete darkness. "Nothing is as devastating as intense light," Broshi said. "Every housewife knows that." Dehumidifiers, working in tandem, keep the rooms at between 50 and 55 per cent relative humidity, considered ideal for preservation purposes. "Like human beings, the scrolls thrive on moderate humidity, the kind we find most comfortable for people," Broshi said. "We think we have found the right preservation ambience. If it is not — and no one can say for sure — we will find out through our monitoring." Museum sources said some experts had suggested placing the scrolls in helium-filled glass, as has been done with the original of the United States Declaration of Independence. But because of the length of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the very large number of fragments, this would be highly prohibitive and cumbersome. Moreover, Broshi said, helium often leaked from its containers. The gas is designed to prevent bacterial activity — but the real danger to the scrolls is not bacteria, but rather the degradation of the collagen into gelatine, an irreversible process. Each year, almost 750,000 visitors pay homage to the Shrine of the Book, making this the second most popular tourist site (after the Western Wall). But they do not see all of the scrolls. In fact, those in poor condition may never be exhibited. Even those sensitive to light but otherwise healthy will also lie hidden. No matter. The little that you can actually see is enough to fill your heart with untold wonder and fascination as you delve into the secrets of a sect of ascetic believers who, as one observer put it, unlike us, with "our spiritual uncertainties", "were so clear about the difference between good and evil".

Proximity factor

Although the Armenian community had no direct role in the discovery or propagation of the Dead Sea Scrolls, they were a heartbeat away from the action a lot of which transpired on or very close to their turf. The St Mark Syriac onastery where the Scrolls were domiciled for a short time, is situated at the periphery of the Armenian Quarter, and abuts homes of residents of the Quarter.